I’ve put together an interactive map of the region plus a logistics section at the bottom of the page because there’s just too much info to squeeze into the body of the blog post.

Calling the Tigray churches Ethiopia’s best kept secret would not only be a cliche, but an enormous understatement. The Tigray churches are an exceptional combination of culture, history and nature, yet they’re unheard of by most visitors to Ethiopia. This isn’t a new phenomenon–the churches, many of which are over 1,000 years old, were only known to their immediate communities until the 1960s. Since then, new churches have been ‘found’ every few years, which is hardly surprising given that they’re often hidden on remote mountaintops and cliffs.

Just reaching the Tigray churches, which often involves hiking and rock climbing, is an adventure in itself. Once you’ve made the journey into the church, you’re then greeted by vivid frescos, antique religious artifacts, and a truly unique variety of architecture. Exploring the rock-hewn interiors is awe-inspiring, and then there are the sweeping views to be had. In all, the experience is incredible.

But what makes these churches even more unforgettable are the people–the priests, the monks and the lay churchgoers. Weather its being given a passionate demonstration of a centuries-old door lock by a priest, sharing a plate of injera with a group of old ladies, or drinking a cup or three of homebrew with a Kalashnikov-wielding monk, the hospitality of the Tigrayan clergy and churchgoers is nothing short of humbling. This is the hospitality of an ancient Christianity, one which was practiced in these pockets of the Tigray Region unspoiled by outsiders, be they monarchy or missionary.

Without a doubt, these churches are the most amazing places I’ve ever been.

My first port of call in the Tigray Region (after Axum) was not a church at all, but rather a monastery. It’s said that when Abuna Aregawi, one of the nine Syrian saints who introduced Christianity to Ethiopia, set out to establish the monastery of Debre Damo, a serpent descended from the mountain top to pull him up under the guidance of angels. Nowadays, the 6th-century monastery remains upon the flat-topped mountain; the snake, however, does not. In its place is a tattered leather rope, the sole connection between the all-male residents and the outside world.

The monks on the ground nonchalantly wrap the rope around my waist and before I know it the monk at the top is pulling me up the 15m cliff. But the rock is smooth, having been worn away by centuries of monks and pilgrims, so instead I’m really being pulled up while my feet pretend to hold my weight. Being more like an enormous lasso than a harness, I have nothing but my arms to cling on for dear life.

Once I reach the top, two elderly monks wave me over to another cliff to eat dried chickpeas. The individual beans are as hard as rocks, yet the toothless monks devour them. It’s at this point that I’m reminded the clergy tend not to speak any English, although really it was my Tigrinya which was lacking. We sit, smiling and grunting, exchanging what is effectively gibberish with one another over handfuls of chickpeas. The atmosphere is serene: no cars, no music playing, and no one speaking loudly.

After a while, another monk calls out and my two new friends beckon further up the mountain towards the monastery itself. As I wander through the gate, a man sitting on the veranda of one of the more recent additions to the complex calls out to me. Same story: no English, no Tigrinya. This time legumes aren’t what’s on offer, but rather a suspicious-looking jug. And unlike the priestly robes of the other two monks, my new friend wears camo and has an AK-47 slung over his shoulder.

Of course, AK-47s are ubiquitous in this part of the country, with farmers inheriting the enormous stockpile of arms from the deposed Derg regime. But this is different: we’re walking distance from a non-existant border with Eritrea, and violent skirmishes do break out occasionally. Just two months after I visited, several locals were tragically killed in the vicinity of Debre Damo. So although, like most Aussies, I’m afraid of basically all guns, I don’t blame these monks at all.

The gun-toting monk takes a large green cup and rinses it with murky-looking water from another jug. He then fills it to the top with a mysterious, opaque liquid with specks floating across the surface. With my friend watching eagerly for my reaction, I take a sip. Similar to white wine, except warmer, and with bits in it. It turns out the drink is tella, a traditional beer brewed from teff, a grain omnipresent in Ethiopian cuisine. It’s gross, but the monk’s generosity and hospitality more than makes up for it. And who am I to turn down free booze anyway?

Three cups later and another monk comes over to show me around the complex. We wanted up the bell tower, where he shows me each of the goatskin drums used for celebrations such as Timkat or Gena. I’m then ushered main building. Built in the 500s (that’s not a typo), the stone and wood structure is probably the best-preserved example Axumite architecture. Unlike other monasteries and churches in Ethiopia, very little has been added or altered by way of renovations.

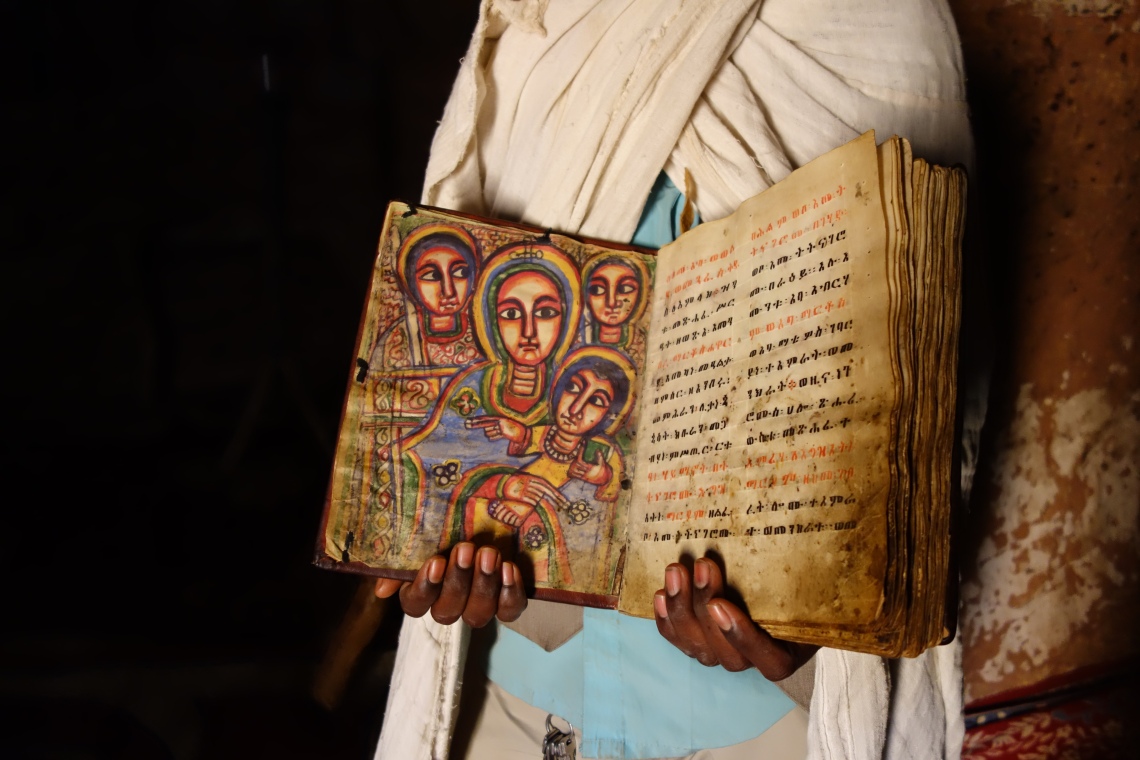

Inside, a ceiling of vivid frescos is flanked by intricately-carved eaves of the finest wood. They’re barely lit by slivers of sunlight coming through the open door and porthole windows. The hum of another monk pierces through the darkness–I look towards the corner to see him curled up and reciting verses from a hand-bound bible. It’s only fitting to witness such a time-honoured act of devotion in the best-preserved example of ancient Axumite architecture and tradition; a stoic testament to the once-mighty empire of millennia past.

Eventually, it’s time for me to go, so I head back past the unkempt cacti to the rope, where the monks hoist me down gently, with my shoes coming down separately (you’re expected to “climb” with bare feet, even though there’s nowhere for your feet to grip). This near-silent tour of a mountaintop monastery is one of my most vivid memories from Ethiopia. It’s not every day you get to drink a traditional homebrewed beer with a Kalashnikov-wielding monk at a 6th-century monastery atop a mountain in the middle of nowhere.

After a quick lunch of ful in Adigrat, I continue on to the churches themselves. Numbering around 120 in total, the Tigray churches were constructed between the 4th and 13th centuries. A small handful were witnessed by early European missionaries and explorers in the region, but other than that, the remaining 115 or so churches were only known outside of their immediate communities from the 1960s! It’s not surprising, considering that many are so well hidden in the cliff faces.

The first of the churches I visited was Petros we Paulos, an all-white church perched a narrow cliff. It was only accessible by climbing directly up the cliff until a makeshift ladder was built in in the 2000s after a local woman fell and died while climbing up. Death is never far from this church, however, with piles of pilgrims’ skeletons to be seen all around the church, much like at Yemrehanna Kristos.

This church is one of the few to be sort of free-standing rather than carved into rock. The result is a wood, stone and mortar design reminiscent of the Greek islands, making it a particularly atmospheric place to soak up the sweeping views. In contrast to the stark, white exterior, the interior is covered in traditional frescos and has very little light (natural or otherwise).

In the cliffs immediately beside the church are piles of dishevelled skeletons and skulls–the remains of pilgrims who’ve made Petros we Paulos their final resting place over the centuries. From here you can fully appreciate the expansive flat planes of the Tigray Region which are punctuated with jagged outcrops and cliffs. Yes it’s mountainous, but not in the typical sense.

As I’m hobbling back down the ladder, both the priest and the deacon silent overtake me by more or less jumping down the cliff face. It’s pretty insane how goof the locals are at climbing, especially considering the newer church down below is now more frequently used.

A couple of cliffs down from Petros we Paulos is Medhane Alem Adi Kasho, a rock-hewn church with a large cemetery out the front. This is one of the larger Tigray churches, with a high ceiling and numerous aisles. Inside, different pillars (carved out of the rock) are stained with honey and milk. This is from local tradition, which deems the church itself to have healing powers. Thus when people are sick, they consume milk or honey off the church’s columns.

Particularly interesting in this church was the locking mechanism, which is an ingenious series of rope and blocks which doesn’t require a key. The priest was particularly proud of this feature, which meant a lot after he was at pains to share the significance of the milk and honey stains with me. He even unlocked and locked it a few times so I could view the mechanism from both sides of the door! Sadly, my photos do it no justice.

Just outside the church is a newer building. While waiting for the priest to make his way up the hill, three old ladies invited me over to share their huge plate of injera, as well as some more tella. As usual, we shared no common language but they were clearly excited to see a foreigner take interest in their local church and made every effort to make me feel welcome.

This injera was borderline stale and the berre berre was one of the worst I’d tasted. These women were clearly poor. If being offered food and drink throughout the Tigray Region wasn’t awe-inspiring enough, the immediate willingness of these ladies to share what little they had with me was truly heart-warming.

After visiting these churches I headed to the nearby town of Hawzien (also spelled Hawzen) to spend the night. The tiny town is basically one intersection with a couple of blocks in each direction, but its prime location and the welcoming locals make it an essential pitstop in the Tigray Region.

Dusk is a pleasant time in Hawzien. The whole town seems to potter about in this grey area between working and dinner. I spend my time wandering the handful of streets. Aside from the market, which was mostly packed up by the time I got there, there’s not much to see. But this is one of those quaint places where human interaction is the highlight. Everywhere I went, people waved and said hi.

When I went to have my daily spris juice that I had grown so fond of in Ethiopia, the guy across form my in the café went and bought barley seeds to share with me. When I walked down the street, people would call me over and offer me eve more types of seeds! This is a town of fucking birds, but I wasn’t complaing. My only regret was eventually saying no–I was starting to fill full from all these fricken seeds, but at the same time I which I could’ve tried all the ones I turned down. Either way, grateful doesn’t begin to describe how I feel towards the people of Hawzien.

After trying ful in Axum, I decided to try its sister dish: feta (pronounced fata). The choices for restaurants are all around the central roundabout and they all look pretty similar–dim lighting, rickety furniture, dirt floors in the front sections, and of course, blaring Ethiopian music. This quaint atmosphere is complemented by an even quainter dining experience.

After pointing at a painting of feta on one of the restaurants’ awnings, the waiter ran into the kitchen and came back out with a bowl and three fresh bread rolls. He then started ripping them apart with his bare hands, throwing the pieces into a bowel. I suddenly realised that everyone else around me was doing the same thing for themselves, but when I tried to help the waiter with my bread has more than happy to put on a demonstration for me instead. I normally hate having to prepare your own meal at the table, and the deconstructed breakfasts popular in Sydney are particularly bullshit, but this was actually hilarious and really fun. When all the bread was torn, the waiter whisked off to the kitchen again.

When my bowl came back, the bread pieces had been saturated in the same fava bean paste found in ful. As expected, the flavour was just as delicious as ful, but the texture was something completely unique. The bread was slightly squishy, slightly chewy, but not particularly damp. It was light–almost fluffy–but extremely filling. Had I not seen the original bread rolls, I would’ve thought it was marinated tofu or something.

Not far from Hawzien is Abuna Yemata Guh–the most “famous” of the Tigray churches. Saying this church lives up to what little hype there is would be a sick and convuluted understatement. I had extremely high expectation after seeing photos, but Abuna Yemata Guh exceeded every one of them.

For starters, the mountains it’s perched on are stunning. Getting from the nearest road to the base of the mountains takes about half an hour. I wandered in and out of dried up gullies, avoiding aggressive dogs along the way. At the base of the mountain, the path becomes rocky. The ascent is precarious enough at first, but then comes the best part. To reach Abuna Yemata Guh, you have to literally rock climb, scaling several cliffs using centuries-old footholds. I rock climb and abseil at home, and this was still one of the most exciting rock-climbing experiences I’ve ever had.

The first time I visited it was early so I could scale alone, but the second time I visited there were a handful of scouts who insisted their help is compulsory and expected a tip. You can apparently also borrow a rope from a nearby town if you’re afraid of falling, but none of this takes away from the hairiness of the whole situation. I’ll talk more about these logistics towards the bottom of the post.

Once I reached the top, I waited for the priest to come. The deacon and I gazed across the vast Tigrayan expanse as vultures circled the rocky outcrops we sat on. The only sound was that of the wind. Like Debre Damo, this exhausting climb is a beautiful act of devotion so it’s only fitting that the destination is so tranquil. The Tigray people don’t fuck around when it comes to designing churches.

Finally the priest arrives, and he leads me around more cliffs. They’re about a metre wide and 200 metres high–high enough that falling would probably mean death–but thanks to the tranquillity of it all I’m not afraid. We reach the door which opens directly into the rock face. Inside is a cave of some of the most beautiful frescos in the country, in a totally unique style to boot. The thing is, it’s not actually a cave. Because of the vastness of it all, it’s so easy to forget that every church was carved by hand using early chisels. Coming up he to visit is difficult enough, so I can’t even imagine doing labour up here day in, day out.

The priest himself, like the others, was a really nice guy. Because of the precarious location, the church decided that the priest had to be young and fit (even though the entire local population apparently still use it daily). Thus he was only 21, which was really cool seeing as I was 19 at the time. He was more than happy to explain all the figures and stories depicted in the frescos and even shows me his ancient, goat-skin bibles with Ge’ez calligraphy.

Abuna Yemata Guh is by far the most breathtaking attraction I’ve ever visited, yet sadly it’s relatively unknown to domestic and foreign tourists alike. I enjoyed it so much that one afternoon in Mekele a week or so later, I decided to catch a bus back to visit it one last time. I brought with me another solo traveller from Canada who, like most, hadn’t even heard of the Tigray churches. Suffice to say, in our very brief visit (we couldn’t miss the last bus back to Mekele!) he agreed that Abuna Yemata Guh had been the highlight of his two-week trip to Ethiopia. That’s saying something.

A few mountains away is the church of Maryam Korkor, which has easily one of the largest interiors of the Tigray churches. The hike up to the church begins in a narrow crevice, where you climb up fallen rocks and boulders like steps. Once you’ve gained some height, the track winds around the cliffs giving breathtaking views of the area.

The exterior of the church is actually an extension that was added in recent centuries. Most people consider it to be a blight, but I can’t help enjoying the way it protrudes out of the rock so quaintly. Inside is more ornate frescos and beautifully-carved ceilings and pillars.

Maryam Korkor was also the only one of the Tigray churches where I met other tourists. In this case, there were two or three groups. Although it did make the experience less intimate than at other churches (you could here their camera shutters, the priest wasn’t fawning over me as his only guest, the doorways are blocked, etc.) I’m glad that more people are experiencing these amazing places of worship and devotion.

On the other side of the same mountain is Daniel Korkor, a tiny, one-room church of little cultural, historical and artistic significance. What is significant, however, are the amazing views form the narrow cliff which leads to the church. Much like Abuna Yemata Guh, the cliff where Danial Korkor is perched is precarious and sheer.

After touring around the Tigray churches I ended up in Wukro, home of the church Wukro Cherkos. However by this time I’d seen enough for two days, and this church looked less impressive from the exterior anyway. However now that I’ve left, I’m hungry for more again! One day I will return, revisiting some of the Tigray churches I’ve already been to and visiting many new ones too. One thing I can say about Wukro is they serve a mean special ful!

It’s sad that these churches are so unheard of and seldom visited considering the fact the priests are more than happy to accommodate tourists (for a small tip, of course). Given how many there are, and how unique each one is, I don’t see an increase in visitor necessarily ruining the feeling of isolation and serenity that I felt as the only visitor of the week in each of the churches I visited.

Consider the fact these 150-odd churches were unknown to outsiders until the 1960s. Even the Emperors of Ethiopia had no idea they existed! Over the decades, more and more of the Tigray churches have been discovered made known to the outside world. Surely in a region as remote as this, where the international border between Ethiopia and Eritrea is both undefined and still technically a warzone with infrequent clashes, there are more churches out there which are only known to their immediate communities. Maybe I will visit one of those next time…

map

Logistics

Here is a map of the Tigray churches I’ve compiled from several guidebooks as well as a map I found in Axum. As far as I know it’s the only interactive map of the churches, and the most complete one across all mediums. It is zoomed in on the main clusters by default, but if you zoom our and move around you’ll see farther afield churches too.

I have marked the churches I visited in my post with stars. Related attractions in the region–the monastery of Debre Damo, which I talked about above, and the temple of Yeha which I chose to skip on account of it being covered in scaffolding–are marked as diamonds. All green pins are those whose locations are accurate; you can use this map to take you directly to each church. Those pins marked blue are in the general area of the church, but by no means accurate.

If you have any info to contribute to the map please let me know in the comments! I want to share this spectacular region with the world, but that’s only possible with collaboration!

As you can see above, some of the churches are in towns, meaning you can take a bus or minibus to that town and just walk to the church. Those which are more remote can be visited form the nearest town by tuk-tuk. You’ll have to haggle a little bit and make sure you agree on a waiting time, otherwise you’ll be stranded! Alternatively, you can find a driver in Axum or Mekele (and I imagine Adigrat and Hawzien too) to take you around to the various churches.

Finding the churches once you’re there is another issue. However at some of the more popular ones you’ll be approached by a boy or young man claiming to be a deacon. These are legit, and they’ll lead you to the church and call the priest to unlock it for you. You’ll have to pay them a small tip for this. Most speak pretty decent English and once inside, they’ll explain the frescos to you and answer any questions you have. This incldues the stories of when the church was first constructed, and when the paintings and any extensions were completed (both were usually done in later centuries). They can also interpret for you and the priest.

To enter the church you must also buy a ticket from the priest, however this money goes to the church as an institution, so you’re expected to tip the priests a similar amount for their efforts. Usually they’ll have to make a long walk from their home down below to the clifftop churches, and on top of that many will be very accommodating in showing you around, showing off their church’s treasures (think ancient bibles and crucifixes) and allowing photography. So be fair and give them a decent tip.

Some of the churches with more demanding climbs will also have self-proclaimed scouts. They’ll help you up regardless of whether you accept their assistance, and it can be annoying sometimes when you’re hanging off a cliff face and they start moving your feet into higher footholes without warning. Again, you’re expected to pay, and because they don’t take no for an answer, you’ll be recieving their services whether you like it or not.

These fees do add up pretty quickly, especially since you’ll hardly want to stop at one or two churches, but it’s still amazing value when you consider how great these churches actually are. Just trust me!

For the hikes make sure you have sturdy shoes. Although you’ll have to go barefoot in the actual rock-climbing sections, and of course remove your shoes when you enter the church. Also bring water, since the churches are usually pretty remote.

Most guidebooks have good info on the churches, but nothing is really complete. No matter what, you’ll still have to ask locals for info on directions, transport, or even which churches are worthwhile visiting.

If you have questions about literally ANYTHING, feel free to ask me in the comments below!

![abuna yemata guh tigray churches ethiopia travel blog (2) Following the deacon along the sheer cliff. [Extremely Hannah Montanna voice] It's the cliiiiiimmmmbbbbb.](https://newfacesnewplacesblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/abuna-yemata-guh-tigray-churches-ethiopia-travel-blog-2.jpg?w=755&resize=755%2C503&h=503#038;h=503)

Hi, i’m making the trip to ethiopia this december, and i’m really interested in those churches, problem is i’m afraid of climbing like that without support and i have 0 experience climbing, is it safe to do such a thing for someone like me? i’m averagely fit nothing exceptional, thanks!

LikeLike

If you are feeling nervous, you can usually ask the deacon to borrow a climbing rope at extra cost. There will also often be scouts who will help you climb. These people know the easiest ways to climb to each church and will make sure you get up safely. Also keep in mind that elderly people climb to many of these churches on a regular basis!

But I don’t think physical aspect is the hard part, but rather the mental aspect of climbing high up without a harness. If you can climb a tree, this will be easy for you! And even if you can’t, you would probably still be able to climb these cliffs!

Of course, not all of the churches require climbing. Some just have a steep trek, and others are in towns and very accessible. Although you do need to climb a bit to see the best churches like Abuna Yemata Guh.

Have a great trip 🙂

LikeLike

Hey,

Just wondering if you had any more details on the cost of the tuktuks or drivers? Also how much for the tips for the helpers/priests and entry fees? And finally how did you go finding accomodation in Hawzien?

Thanks so much for the write up, will help immensely when we visit next week some time.

Cheers

LikeLike

I get asked the first questions quite a lot but unfortunately it was so long ago that I couldn’t even give you a ballpark figure. But I’m very much a shoestring traveller yet I still remember the churches as being excellent value, although haggling is to be expected for transport/helpers.

The deacons will typically come to you as you approach the church so it’s not as if you can ask around and find the cheapest one. They live nearby and hangout in the area, and of course if you look foreign or even just wealthy then word will spread pretty quickly!

In Hawzien there are a handful of very cheap hotels which is where I stayed but just out of town there’s also the Gheralta Lodge which is meant to be the most luxurious resort in the country! Anyway it’s a very small town so it’s impossible to miss the hotels.

If you want to research the cost of drivers you can do so easily in Axum or Mekele. I would recommend asking in person rather than ringing agencies because that’s how they price gouge foreigners by hundreds of dollars. As for tuk-tuks, you’ll have to haggle in the small towns closer to the churches themselves such as Hawzien. However I’m not sure if it’s possible to get a tuk-tuk to somewhere like Debre Damo or the more remote churches. Hopefully the map will be helpful in sorting this out.

Anyway have a great trip and let me know if you have any more questions!!

LikeLike

Of course, I’m excited by the beauty, history and cultural significance of these incredible churches and monasteries but I think what most struck me reading this was your interactions with the local monks and others, such incredible experiences, these are what must have truly made the trip most memorable!

LikeLike

You’re spot on, Kavita! I’ll never forget the warmth and hospitality I experienced from everyone in the region. They taught me more about Tigrayan culture than any attraction could.

LikeLike

Honestly Zac – Your blog post is amazing, your pics are incredible – I really loved reading this post! I didn`t know that Ethiopia is so cool – thanks for sharing this with us

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed Martina!

LikeLike

Wow, putting in a little (or a lot of) effort has rewarded you with the most amazing experiences! Your description of the kalashikov wielding and drink-proffering monks fascinated me – great post Zac

LikeLike

Cheers Em! It such an unexpected experience that I just couldn’t help but share!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both the vistas and the vivid frescoes inside the churches are breathtaking. Ever since I’ve read about these churches back at the university, I’ve been wanting to explore them. And now your post with all the extensive details just reminded me that Ethiopia is still on my bucket list, and that I should go there soon. I’m just not sure if I’ll dare hiking up the cliffs! Guess I need to work on my fear of heights before going there.

LikeLike

I felt the same way when I first read about the Tigray churches, which is what motivated me to go even though they’re a bit off the beaten track. They still exceeded my expectations, and the rock climbing only added to that! Glad you enjoyed the post!!

LikeLike

Indeed an incredible experience, yes it is just sad that this church was not visited often by other tourists because it is barely known. Thanks to this post of yours, for sharing about this enormous church of Ethiopia. I really admire the people here for taking good care of the church and its old relics also, how they accompany you to see how beautiful this church is, I really admire the people there. I love the photos, they really are breath taking.

LikeLike

Thanks Ghia! It is indeed admirable how the people care for their traditions and history.

LikeLike

How amazing, I’m in love with your photos! This sounds like such an amazing trip! It’s so interesting that the only way up to Debre Damo is with a tattered leather rope. And all of the views are incredible!

LikeLike

Thanks! The rope made it so much more exciting haha

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! The view of Yemata Guh is simply stunning! It’s nice you got a such an experience with practically no other tourists there. You got to try many new things, but it’s brave of you to go up the rope. I’d be so scared to do it haha! I’m sure you’ll always remember that though!

LikeLike

Cheers Edith. It was great to get out of my comfort zone & definitely my most memorable experience traveling!

LikeLike

That looks like a real adventure, very cool. What photo gear are you using, real nice snaps!

LikeLike

It really was! I just used a Sony RX-100, an iPhone 6S and a whole lot of luck hahaha. Thanks!

LikeLike

Wow, wow, wow! I am in awe! This adventure looks incredible! Dangerous, heartwarming, and just a once in a lifetime experience! I can’t believe how unknown these incredible churches are. And they’re so old! I’m mindblown. How did they even build the churches up there so high?! Incredible article, thank you for sharing

LikeLike

Thanks so much, couldn’t have put it better myself! So glad you enjoyed, hopefully one day the churches will be much more popular!

LikeLike

The mountains look absolutely spectacular. I have yet to get to Africa but wow, i cant wait! It sounds like the generosity you experienced is beyond what we experience in the west. Kindness is such a lovely quality! I’d be a bit dubious about that beer too, it looks…interesting! But glad you had a great experience.

LikeLike

Cheers Rachel, as you say that beer was unusual to say the least but the monk’s generosity in giving it to me more than made up for the flavour hahaha

LikeLike

I really enjoyed your post. On Sunday the BBC had a comedian visiting Ethiopia and he visited the remote church on the top of the mountain. I have never seen such a beautiful place. Thanks for sharing x

LikeLike

Thanks Aliyah, glad you liked the post. I seriously love it when this part of the world is featured in the media! It’s chronically underrated so I think it’s fantastic that it was on somewhere as big as the BBC

LikeLike

Hi Zac ! Such a great post ! Well documented, stunning photos and extremely useful guide. I’m currently planning a similar trip, as part of a video project. I’m a bit worried about not being able to have intimacy and time to discuss as equals with the priests and pilgrims over there, so I’m wondering what’s your impression on engaging with people in this area. Ideally, I would like to spend quite a bit of time with one or two priests and take videos where they explain their relationship to faith and history. Do you think it’s feasible? How expeditive where your visits and interactions with the priests usually?

Best !

LikeLike

Hey Lou! Glad you found the post helpful!

My visits were fairly informal. I just turned up in the general vacinity of the church and eventually a deacon would approach me as a kind of fixer as the priests are typically at home. You could also get one of the tour companies in Axum or Mekele to assist with this process.

The most important factor in what you describe are the deacons I think. They’ll be the ones who interpret between you and the priests who never speak English, so maybe check that their English is decent and that they have good knowledge of the church. The priests themselves are friendly and generally very willing to share their churches and will be able to answer any questions you have.

There are very few other tourists (I only bumped into others at one church) so that won’t affect the intimacy. Just don’t turn up during a church service if you want to spend one-on-one time with the priests.

I think most priests will be willing to be videoed for longer periods, provided you give them a proportionate to. It might even be best to discuss this upfront before you commence filming. Tips are expected from all tourists so for a project like yours it should be bigger than usual. Be sure to discuss what can and can’t be filmed too–each church’s replica of the arc of the covenant, is totally off limits.

Finally, it would probably depends on what churches you choose. At more accessible and therefore more popular churches such as Maryam Korkor and even Abuna Yemata Guh, the priests will likely be a bit less enthusiastic to a curious foreigner and be jaded towards being asked these kinds of questions all the time. That’s not to say they’re terrible choices; the priests I met at these churches were still patient and lovely.

Good luck, I’d love to see your project when it’s done!!!

LikeLike

Just wanted to let you know that this post was very helpful to me while researching my trip to Ethiopia (March 2019). I’d have to agree that the churches and natural sights in Tigray were probably the most memorable parts of the four weeks I spent in the country. You might be surprised to know that things are changing very fast though. Seems like Hawzien is no longer the sleepy town you described as there are new tour companies and facilities popping up left and right.

And on a side note, when I visited Simien national park, I was a little bit sad to find out that all the villages within the park limits had been forcibly moved out, following the directions of UNESCO (I recalled your post about stopping for coffee in one village).

Anyways, thanks for the detailed descriptions of places and logistics.

LikeLike

Hey Jonas, so glad you loved the Tigray region as much as I did. And glad that you found my post helpful 🙂

I’m not surprised at all that Hawzien is now a tourist hub, given how spectacular the area is. I was there in January 2016 (a bit earlier than the timestamp on this post implies) but it’s still a short time for the growth you described! Hopefully it’s happened in a way which has created opportunities for locals while still avoiding overtourism at the sites themselves Maybe you could shed some light on this?

It’s also a massive pity that UNESCO forcibly removed the villages in the Simien Mountains. They didn’t seem to affect the environment that much–they were mud huts without electricity or running water–and even if they did surely the could’ve reached some compromise, no?

Either way, tourism is clearly changing this country very rapidly. Really appreciate your insights!

LikeLike

In terms of changes in Hawzien, the impression I got is that the locals are quickly becoming aware that their historical churches have the potential to become major tourist attractions, on the same level as those in Lalibela. So unsurprisingly, one easily runs into young entrepreneurs trying to push tours through their own or their friends’ agency or others hoping to make quick easy money from the referral.

Abuna Yemata specifically seems like the new thing to do for a lot of visitors and many agencies in Mekelle and Adigrat are now offering 1 or 2 day “Tigray Tours” many of which spend a night in Hawzien.

Also, it appears that hiring a local guide is now a formal requirement for most of the churches, while the ‘scouts’ who wait around for tourists at a couple of the more popular ones have reportedly been getting pushier (although my experience with them was not too bad). Even the elderly priest at Abuna Yemata got slightly argumentative about getting a larger tip than normal.

I was told the numbers of tourists are doubling or perhaps tripling ever year. Therefore, the demand is being answered with more tour companies and better accessibility. This is not necessarily a bad thing. For example, it is worth noting is that if you meet the right persons, it is fairly easy to arrange multi-day treks and staying overnight in the small villages around Gheralta (allowing one to visit several churches by foot) or camping up on the cliffs near Maryam Korkor to witness the Sunday mass during the early morning hours.

From the local communities perspective, it looks like most are happy to receive foreigners since many are seeing a tangible difference in their income. I met a happy group of men on their lunch break who offered me and my guide some roasted barley and tallah (the beverage you write about 🙂 ) – they explained that thanks to the entrance fees of Papaseit Maryam church over 3 years, the community was able to purchase a mini-van!

In any case, I had a great experience visiting the area. Every church is different from the next one and truthfully, none of them really felt overcrowded. Tigrayans in general showed me great hospitality and there were plenty of genuine interactions everywhere I went.

One last thing, as a side note… You wrote that Daniel Korkor has “little cultural significance”. I thought I’d share with you a bit of what I was told about this place. Actually, it was never intended as a church. This was the dwelling place/meditation cell of the monk who built Maryam Korkor. This is why it is hardly decorated and artistically unimpressive. However, for the faithful, the site is quite significant since they go there occasionally to collect ‘holy dust’ from the spot where according to legend, the monk spent countless hours in deep prayer. Hearing this story while standing within the small cave helped bring it to life.

LikeLike

Your insight is really interesting, so thanks!

While I can’t stand touts, if that’s what it takes for the area to become more accessible in general, I think that’s a great thing. I would’ve loved to have visited some of the more remote churches but at the time it just seemed like too much effort. Camping on the cliffs also sounds amazing! From your interaction with the locals, it seems people are just as friendly and welcoming which is fantastic… people there really do love sharing their snacks. It’s also fantastic that the community could buy a van!!! It kind of reminds me of the community-run TESFA model of sustainable tourism, which already had a decent footprint in the area from trekking tours. So I’m glad that despite the increase in visitors, you still had a great experience and didn’t find any of the churches overcrowded!

Thanks for the anecdote about Daniel Korkor too! I had no idea it was that special, and I wish I’d known at the time hahah! It would totally make the place feel more hermetic knowing this.

Finally, I’ve been researching a bit more about the villages in the Simien Mountains which you mentioned. UNESCO indeed instructed the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority to push the “voluntary” relocation of the villages, but it seems as if they were pushed out without much choice. Supposedly up to $8 million is being set aside for the compensation of all of the families, but nothing is being done to help them transition to alternate livelihoods. I decided to look at historical satellite imagery, which I compiled into a GIF. You the village of Geech/Gich/Gitch, where I was invited for coffee, here:

Just one hut remains. The residents of this specific village were relocated to Debark, which you’ll probably remember as the place where you have to register before entering the park. The town doesn’t really seem like somewhere where you can practise a pastoral lifestyle. Tessema, Jungmeier & Huber (2012) studied the relocation of another nearby village which was the model for Gich. They found that while residents were happy with the new town facilities, their livelihoods were greatly affected and grazing actually increased in the park to compensate for this economic upheaval. So yeah, even though they were compensated, which is the bare minimum, it seems like they didn’t have much choice and now their age-old livelihoods have been turned upside down.

LikeLike

Certainly, I’d imagine that if they had the choice, most would have stayed up in the mountains. My impression from talking to people from rural communities is that while some of the youth would rather get a proper education and perhaps live in a larger town, the older generations are quite content with the traditional herder lifestyle even if there aren’t many opportunities for increasing material wealth. Personally, I found Debark to be quite an unattractive place – it would be difficult to move from the ancestral mountain scenery to such a town without a good deal of psychological suffering.

When I was in Simien Park, we came across several areas that had been burned down. Although I think the official cause was ‘wildfire’, my guide implied that the fires had been started intentionally in protest. What exactly they were protesting was not entirely clear but it likely had to due with the grazing rights.

LikeLike

Wow,wow,wow…. I st wow!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing. I ran out of time and never got to the northern part of the country. Reading this has re-energized the need to re-visit Ethiopia.

And thanks for reading my blog. 🙂

LikeLike

Glad to hear!

The region was ravaged by a particularly tragic war over the past two or three years but I really hope the peace deal can hold so that people can begin rebuilding.

LikeLike

Wow. Yea, the sound-like stone has been found also around pyramids and they are little wonders…almost imposible. But same soundy efects as stone “sarcofages” in big pyramids, so it´s big chance it was made

LikeLike