There’s a mountainous part of Southeast Asia spanning Thailand, Myanmar, China and Laos that was until recently too treacherous for outsiders to conquer. The countless indigenous ethnic groups who live there have many names for the region. Some white dude dubbed it “Zomia.” But it is perhaps most notoriously known as the Golden Triangle.

Opium had long been grown in small quantities in this region. By the 1950s, holdouts from the Kuomintang army in the Chinese Civil War fled south to Burma and used this opium cultivation as a new source of income. Among the recruits of this regiment was Khun Sa, a half-Shan, half-Chinese soldier who would eventually break away and found his own narcotics army with a ethnonationalist bent.

Khun Sa dialed opium cultivation up massively and funded his rebel army by becoming the world’s biggest heroin drug lord. US Vice-Secretary of State Marshall Green would eventually coin the term “Golden Triangle” to describe this remote, mountainous area during a press conference in 1971. The name has stuck since then.

Tour guides will have you believe that the Golden Triangle is the tripoint where Thailand, Myanmar and Laos meet on the Mekong River. In reality, this spot is just a giant tourist trap of no actual significance. There are two opium museums (one reportedly decent, the other reportedly bad) but this spot is actually quite far removed from where the opium poppies were cultivated.

I wanted to go to the heart of the the former opium country. I wanted to go to Khun Sa’s former headquarters.

In the city of Chiang Rai I found a driver who could take me deep into the mountains, not far from the border with Myanmar. Google Maps has a village marked as the purported military base of Khun Sa’s army in Thailand which I used as a waypoint for our long drive along the ridges.

When we arrived at the hamlet of Mae Fa Luang, we followed the map down some laneways that led out of town and under the protection of trees and thick scrub.

What we found was interesting. Standing there was a bronze statue of Khun Sa on horseback. Locals who had presumably befitted from the drug lord’s largesse and whatever semblance of prosperity he brought to the region had turned the site into a small museum and memorial.

There were a few old buildings scattered around the area. According to the signs on the walls, these huts were once the training site for Khun Sa’s Mong Tai Army. Nowadays they’re filled with plaques and information boards — mostly written in Thai and Shan — which explain the history of the Shan people and their struggle for independence.

The displays painted a history of the Shan people who were once ruled by their own Chao Pha leaders, only for their territory to be carved up by the surrounding nation states. The signboards speak of the ongoing “Shan Revolution” of 1958 and outline the state’s historical constitutional right to secede from Myanmar. Meanwhile, the Shan State is depicted as an independent country on large maps. All of this served to link the princes of the past to Khun Sa’s stint at keeping the region out of reach from kings in Bangkok and generals in Yangon.

The huts themselves were dilapidated. Most of them were locked, meaning I had to find a way to let myself in or just peer through he windows. There was nobody around to let me in. At one point, my driver and I wandered towards some huts in the distance when a lady yelled at him in Thai that the person in charge of letting in visitors wasn’t available.

The Khun Sa Old Camp is a weird monument to a weird history. It attempts to navigate its status as the former heart of a global heroin empire from the perspective of dirt-poor, marginalised village folk who were promised an honest and dignified living by the drug lord himself. Khun Sa built hospitals and electricity infrastructure, and even a golf course for visitors. His ploy presumably worked, similar to Pablo Escobar’s reputation in Medellín.

This corner of the world was the source of 80% of the world’s heroin at its peak. In Washington, the DEA branded Khun Sa the “king of opium” who must be apprehended at all costs. But to many local people, he was and still is a national hero.

Nowadays the region on this side of the border has been pacified by Thai forces. Tea is the new crop of choice, with only a handful of the most remote and impoverished villages daring to grow opium poppies. Seeing how these people at the Khun Sa Old Camp lived so basically compared to those in the adjacent town made me understand why they might not be keen to simply forget the good old days. Law and order hasn’t delivered much for these people; modern Thailand seems to have passed them by.

Due to a number of factors, Khun Sa’s infleunce declined in the 90s. In 1996 he surrendered to the Burmese government, relinquished control of his army, and retired to Yangon with a large fortune and four young Shan mistresses. He died in 2007 at the age of 73.

My next stop was a memorial to the Kuomintang soldiers at Mae Salong. Yes, the same Chinese Kuomintang army where Khun Sa cut his teeth a soldier.

At the tail end of the Chinese Civil War, the 93th Division of the Kuomintang roamed around the border region of Yunnan province. Once the Communists gained total control of mainland China in 1949, the this particular division of the Kuomintang refused to surrender and fled to Myanmar’s Shan State. The Burmese government was not happy with this and more fighting ensued. Meanwhile, the CIA provided the 93rd Division with money and weapons in exchange for making intelligence runs across the border into China. Through this precarious existence the 93rd Division would come to be known as the Kuomintang’s “lost army.”

Eventually, the leader of the 93rd Division led his battle-weary soldiers across the border into Thailand. For around eight or nine years these soldiers fought the Maoist insurgents who were present in Thailand’s remote northern hills. By 1970, the 93rd Division had received the tacit endorsement of the Thai government, which itself was fearful of the spread of communism in the north. The Thai government even reached an agreement with Taiwan — which, don’t forget, was run by the Kuomintang — to manage this battalion itself. Meanwhile, the Taiwanese government began pouring money into development projects in Chinese-populated towns around Chiang Rai.

The Martyr’s Memorial Hall at Mae Salong pays tribute to these soldiers and presents them almost as pioneers in an remote and lawless corner of Asia. It has plenty of information boards in Thai and Chinese about how these holdout Kuomintang soldiers fought back against the Communists from their base in northern Thailand, before settling in the region for good. Some of these information boards had apparently been translated into English by a computer, complete with incoherent rants about the dastardly “aboriginal Miow Communists.”

Historical revisionism aside, the gardens were well kept and the busts of Kuomintang leaders were appropriately solemn. The memorial really did convey that this decades-long conflict had been laid to rest along with the soldiers who lost their lives.

While I was in the area, I also swung by the border town of Mae Sai, which the northernmost town in Thailand. My interest was less Mae Sai itself and more the opportunity to duck across the border into Tachileik in Myanmar.

Remote border areas have always been fascinating to me as they’re liminal spaces (literally haha) where laws are often different, where people are free to indulge what is considered taboo, and where black markets thrive. The mystical and illicit have long thrived in these spaces, and gambling is the natural convergence of the two. It should come as little surprise, then, that many forms of gambling have their origins in ancient divination techniques. And that’s what brings me to Tachileik, which is home to a gigantic casino run by Khun Sa’s favourite son. I imagine this looks very out of place for an otherwise poor, rural area.

Gambling is legal and very widespread in my home country of Australia, but elsewhere casinos typically seem to emerge in the weirdest places, be it the deserts of Nevada, the former colonial outpost of Macau, or the once-broke Principality of Monaco. Surrounded on most sides by warring factions in Myanmar and the Kingdom of Thailand’s stricter laws to the south, Tachileik fits perfectly into this mold.

Alas, when I walked up to the border crossing, I learned that it was closed indefinitely due to the pandemic. Ugh. Mae Sai has a pretty gigantic border market where travelers on either side of the border can take advantage of different retail laws and taxes or whatever, but this was actually pretty boring. I left after a few hours.

My base for this journey around the uppermost extremity of Thailand was the city of Chiang Rai. It’s nice, walkable town with a relaxed atmosphere. Like many Thai towns there are great night markets and good massage parlours too.

Northern Thailand was one of the last regions to come under control of the current royal dynasty in Bangkok. The nearby mountains are home to several indigenous groups — the so-called Hill Tribes — who have lived free of outside control for centuries. Some of these groups have always called these mountains home, while others migrated long ago to flee persecution in remote parts of what is now Myanmar or China.

Nowadays their various ways of live are under threat. Some got caught up in drug cultivation and Khun Sa’s eventual demise, while others are having their traditional lands encroached upon by outsiders, and others are having their way of live decimated by Thai cultural hegemony.

It’s possible to visit some of these villages, but most opportunities for tourists seemed to be like a bit of a human zoo where the primary goal it to take photos of women with long necks. But in the heart of urban Chaing Rai, there is a museum dedicated to these cultures and the issues they now face.

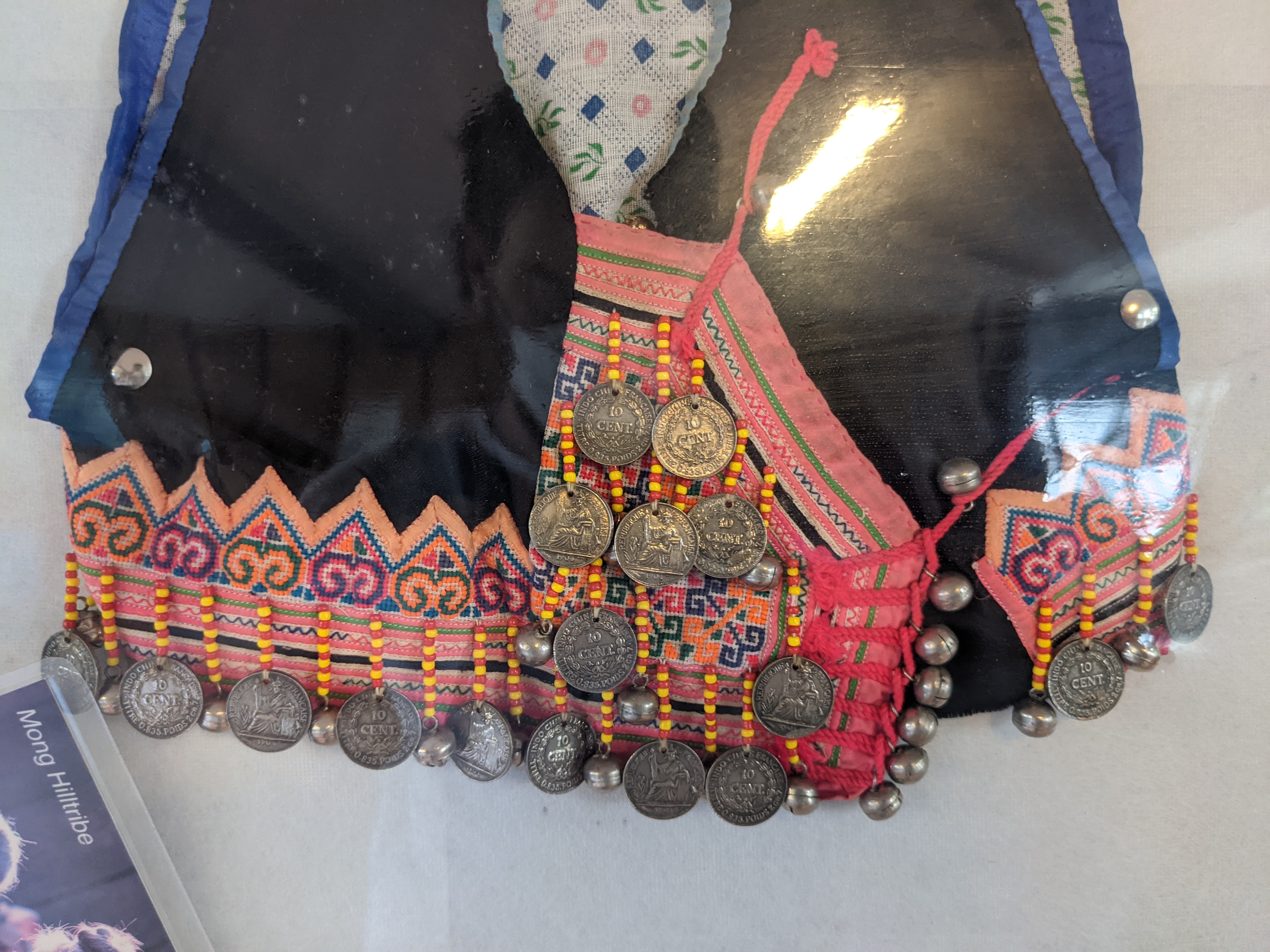

The Hill Tribe Museum and Education Center was established by some foreign dude as part of an NGO that works with these indigenous peoples. The dusty displays are a timewarp back to the 90s, but the information is largely respectful and sympathetic to the perspectives of these different groups. I enjoyed getting this glimpse into the different cultures of the area without going on some awkward photo shoot tour.

Perhaps because of this history, there seemed to be a conspicuous effort to project the role of the Thai royal family and government through public architecture, more so than in other towns I visited further south. One example is the Chiang Rai Clock Tower, which is a gorgeous golden statue that, despite its antique design, was constructed in 2005. You can see a photo of it at the top of this blog post.

Chiang Rai’s biggest attraction, however, is Wat Rong Khun, also known in English as the White Temple. This is the kind of attraction you see all over people’s selfies when they visit Thailand. But these photos won’t prepare you for the majesty to behold in person. I had pretty high expectations from seeing all these photos, yet the temple managed to exceed them when I visited.

Wat Rong Khun was designed by renowned Thai artist Chalermchai Kositpipat, who also designed the clock tower I mentioned earlier. The main temple takes over you a bridge and through three buildings. They’re not huge, but the detail is spectacular. The stark white colour scheme is unique among Thai temples and only highlights the intricate plaster.

Officially, the white signifies the purity of the Buddha and the mirrors symbolise the Buddha’s wisdom and the Dharma. What you can’t appreciate from the photos is that there are mirrors affixed to the exterior — not too dissimilar from the interiors of old Iranian palaces — which reflect the sun’s light in every direction. The end result is otherworldly, and it almost hurts to stare directly at it.

Chiang Rai is a lovely little town, and the surrounding hills are beautiful. Opium cultivation in the region has dropped to negligible levels, with the land now used for oolong tea plantations instead. The town where the Khun Sa Old Camp is located has even been renamed Thoet Thai, meaning the “Village to Honour Thailand.”

Clearly, today is a new chapter. But a handful of people deep in the mountains still long for the good old days.

That was a particularly fascinating read for me right now as I’ve just returned from Southeast Asia, and one of my last stops was Chiang Rai. I love that you ventured into the “real” Golden Triangle; all I got to do was stare at a hazy outline of a series of mountains in Myanmar and Laos from Doi Tung, the Thai Queen Mother’s palace north of the city. As you note, that’s sort of the tourist version of the region anyway. Great post about the area and the White Temple as well.

LikeLike

Much appreciated! I actually regret not taking in enough of the scenery while in the mountains, and that’s why I have barely any photos of the terrain. Chiang Rai just has so much to see and do I guess!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure how I missed this post, but it’s really cool that you got to visit the real Golden Triangle. If I make it this far in this part of Thailand, I would probably be more drawn into the city of Chiang Rai itself — and maybe take too many photos of Wat Rong Khun with its intricate details. I had no idea that this part of Thailand used to host a division of the Kuomintang army, and I must say architecturally-speaking the Martyr’s Memorial Hall does look Chinese.

LikeLike

It’s a fascinating area! Even the buildings in the villages surrounding the Martyrs’ Memorial Hall are made to look Chinese, although I didn’t snap any good pics. Many of the restaurants in those few villages are serving up Yunnanese food rather than Lanna/Thai cuisine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Intriguing read! I had no idea about the Kuomintang connection.

LikeLike